On 28 January 1894, local peasants in Patharughat tehsil protesting against the revenue enhancement of 1892 were killed in police firing. According to British official records the police firing at Patharughat killed 15 peasants and wounded 37 others. These figures are contested by local oral traditions which mention that 140 people were killed in the firing. A martyr’s column stands at the site located in Mangaldoi subdivision of Darrang district in Assam. Colloquially referred to as Patharughator Ran (Battle of Patharughat), the Patharughat peasant resistance has become a part of the local collective memory.

Despite the distinct local struggles like the one at Patharughat, the popular imagination of the struggle against British colonialism in India is limited to the elite bourgeois nationalist movement led by the Indian National Congress. There is a tendency to look at the development of a national consciousness as a linear process. In doing so we fail to acknowledge the role of the subaltern classes and groups. We have to recognise that the anti-colonial struggle had different meanings based on varied spatio-temporal realities of the medley of people rising against the colonial state. Between the Revolt of 1857 and the bourgeois nationalist movement of the twentieth century, diverse forms of peasant resistance challenged the colonial structures of domination at the grassroot level of many small towns.

There is a growing body of literature on the history of peasant resistance in India which broadens our understanding of subaltern political action. A particularly remarkable perspective is presented by Partha Chatterjee in his study of agrarian relations and communalism in colonial Bengal. Challenging the ‘Marxist’ framework on colonial agrarian relations, Chatterjee argues that a community consciousness shapes peasant politics in relation to the state. The community exists in opposition to those beyond the boundaries of the community. However, David Hardiman has noted that community-based resistance does not inhibit the assertions of identity by subordinate groups within the community. Hardiman has identified five chief ‘areas of resistance’ based on the relationships of domination and subordination:

- peasants against European planters; (2) peasants against indigenous landlords; (3) peasants against professional moneylenders (sahukars); (4) peasants against the land-tax bureaucracy; and (5) peasants against forest officials. (Hardiman 1992

The peasant resistance at Patharughat falls under the ambit of the fourth demarcation — peasants against the land-tax bureaucracy. There is a consensus among historians that the most immediate cause for the spontaneous reaction of the peasantry at Patharughat was the increase of revenue rate. It must be noted that the complexities of the agrarian structure under the British Raj, which led to increasing grievances among the peasantry, provided a background to the overt expression of resistance.

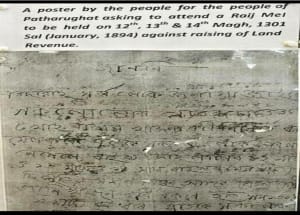

By December 1893 the peasantry in north Kamrup had risen in revolt against the enhanced revenue rates. The village assemblies, known as Raij Mel in Assamese, collectively decided to refuse to pay the land revenue. The peasantry in Darrang soon adopted a similar approach and scattered episodes of violence erupted. In addition, handwritten posters inviting the raij (lit. people) to the village assemblies were pasted in different corners of the villages. Arupjyoti Saikia has translated one such poster in Patharughat. The poster reads:

The Raij has been hereby informed that a raijmel will be held to decide on revenue enhancement of the province. All people are asked to come. Those who will not come will face the punishment given out by raij. The Mel will be held on 12, 13, 14 Magh. The Deputy Commissioner will come, he might reduce the revenue. All should remain together. (Saikia 2010)

The Deputy Commissioner, JD Anderson assessed the situation in Mangaldoi and made arrangements to control the situation. Anderson and his team arrived in Patharughat on 27 January 1894. The next day Anderson ordered the District Superintendent of Police, Berrington to attach the lands of the peasants who defaulted to pay the revenue despite being served a notice. The peasants resisted the attachment of property and Berrington claimed that he had to open fire to disperse an advancing crowd which had gathered.

On the afternoon of 28 January, the peasants gathered on the field facing the rest house in which Anderson was camping. Official estimates suggest that around two thousand peasants had gathered there. The peasants hoped to share their grievances with Anderson and persuade him to reduce the revenue. Even though Anderson interacted with the peasants, he did not accept their demands and asked them to pay the land revenue and stressed not to hold raiz mels. The peasants did not relent and refused to disperse unless their demands were accepted. Anderson ordered Berrington to open fire at the peasants. The crowd retaliated by throwing clods of clay and bamboo sticks at Anderson and his men. After the incident the resistance could not be sustained and the peasants were forced to pay the enhanced revenue in the face of state repression.

The events of 1894 were narrated in the local oral traditions which were collected in a text called Dalipuran. The lore helped to preserve the memory of the peasant resistance. But in the twentieth century the memory of Patharughat was appropriated to shape a distinct Assamese national consciousness. On 28 January 2001 the erstwhile Governor of Assam, SK Sinha inaugurated a martyr’s column at the site. The day is commemorated as Krishak Swahid Diwas (Peasant Martyrdom Day) in the state of Assam.

References:

1. Online articles

- https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/assam-patharughat-1894-peasant-uprising-martyrs-column-7165125/

- https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/bravery-peasants-of-pothorughat-who-revolted-against-revenue-hike-then-killing-inspired-people-of-assam-for-more-than-100-years/article33751363.ece

2. Books

- Guha, Amalendu. Planter-Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam 1826-1947. New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research, 1977.

- Hardiman, David, ed. Peasant Resistance in India, 1858-1914. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Saikia, Arupjyoti. “Landlords, Tenants and Agrarian Relations: Revisiting a Peasant Uprising in Colonial Assam.” Studies in History, Vol. 26, No. 2 (2010): 175–209. DOI: 10.1177/025764301002600203.

The views, information, or opinions expressed above are solely those of the author(s) involved and do not necessarily represent those held by India Lost & Found and its creative community.

Hiya, I’m Abhilash Chetia Wanniang …

Hiya, I’m Abhilash Chetia Wanniang …

Abhilash Chetia Wanniang is an undergraduate student of History at Hansraj College, University of Delhi. His areas of interest include state formation, colonialism, gender relations, Bhakti tradition, Dalit literature, tribal identity, and language politics. He currently holds the position of President at the North-East Cell, Hansraj College. He is also the Content Head of Feel to Heal: A Mental Health Forum.

Hiya, I’m Abhilash Chetia Wanniang …

Hiya, I’m Abhilash Chetia Wanniang …